As content strategists, we spend a lot of time talking to business people about the importance of storytelling to their business. When the subject comes up, a lot of folks get nervous. They say things like, “Well, I’m no Hemingway!” or some other nervous response.

The pressure of storytelling can keep a lot of people from even trying.

But here’s the thing: we don’t have to be Hemingway to be good at stories. Storytelling is part of what makes us human. If you have human DNA, you’re built to tell a story. Unfortunately, some of us give up on our storytelling ability too early. But even if you’re not a professional storyteller, there are a couple of storytelling frameworks that can help you bridge the gap. The two frameworks discussed below will help you regain some storytelling confidence, and start telling engaging stories in business and in life.

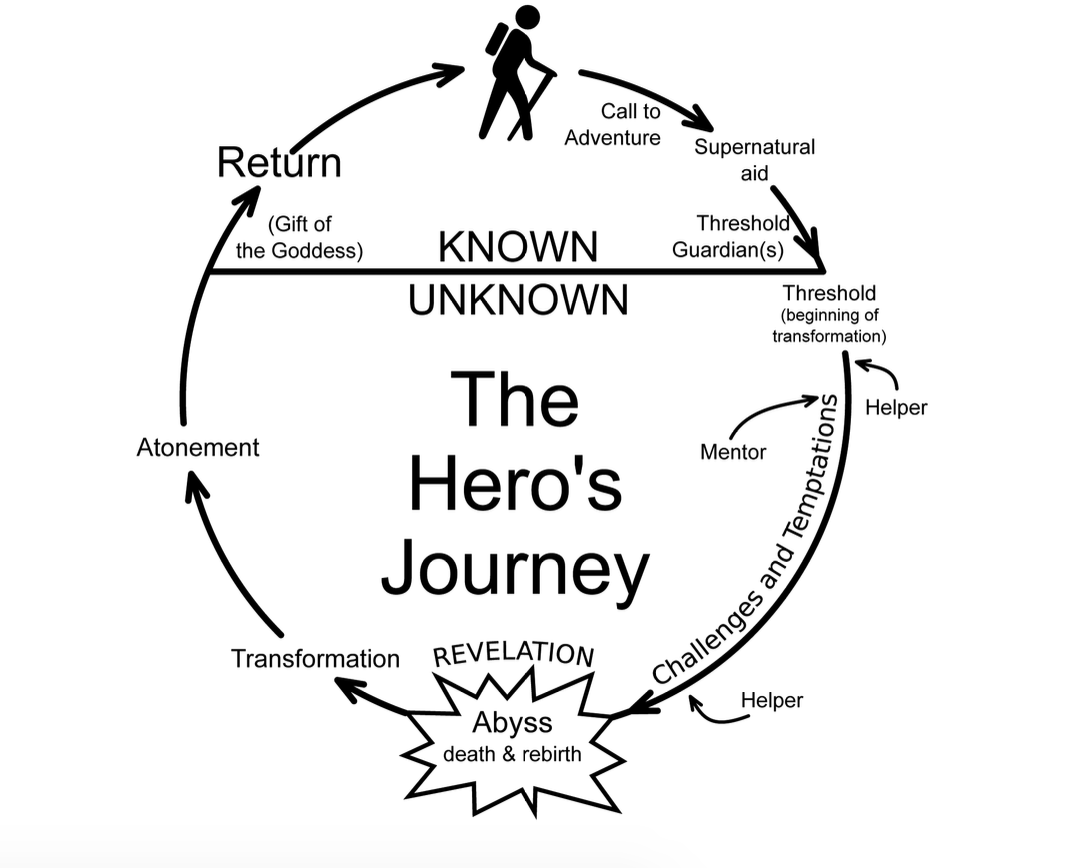

The Hero’s Journey

See if you can guess what story this is.

We have a hero who starts in humble beginnings and answers the call of adventure. She leaves home, gets out of her comfort zone, receives training from a wise old mentor, and then goes on a great journey. On this quest, she faces a bad guy, almost loses everything, but eventually succeeds and returns home having changed for the better.

What story are we talking about?

Is this Star Wars? Harry Potter? The Hunger Games? The Odyssey? The Matrix?

It’s actually all of them.

This is a template for storytelling called The Hero’s Journey. It comes from author Joseph Campbell, and it’s everywhere. It’s one of the most relatable storylines because it basically mirrors the journeys of our own lives. Understanding The Hero’s Journey can give you insight into how to frame your own stories, whether it’s the true story about your company or a fictional story that stirs your imagination.

The following diagram breaks down this Hero’s Journey template, step by step.

We start in an ordinary world. A humble character gets called to adventure and initially refuses, but meets a wise mentor who trains them and convinces them to go on said adventure. They’re then tested. They meet allies, and they make enemies. They approach a final battle and almost lose but, eventually, find it within themselves to succeed. They return home to an appropriate hero’s welcome, transformed by the journey.

Let’s walk through this from the lens of the greatest story ever told.

Yes, we’re talking about Star Wars. Let’s step through a crude synopsis to see how well it matches Campbell’s pattern:

In the first Star Wars film, we begin with the rather ordinary Luke Skywalker. He lives on a farm on a desert planet. One day he meets some robots who need help. They need to find a local hermit named Obi-Wan Kenobi. So Luke takes the robots to Obi-Wan, who basically says, “Luke, you need to go out and help save the universe.” Luke initially says, “No, I have all this stuff going on,” but Kenobi, who becomes Luke’s mentor, convinces Luke that he should go. Kenobi trains him how to use a lightsaber, and Luke goes on an epic space adventure.

On the journey, Luke meets the villain, Darth Vader. He battles evil stormtroopers. He makes friends: Han Solo, Chewbacca, Princess Leia. And then he has to help defeat the super-weapon, the Death Star. Nearly everything goes wrong, but in the end, Luke succeeds in blowing up the Death Star. The last scene of the movie is of Luke getting a metal put over his neck by the princess, who kisses him on the cheek. Now he is in his new home, a changed man, emboldened by the great power of the Force, which he can use on future adventures.

This is the Hero’s Journey, which—modified in various ways—we see repeated in stories throughout history. The simple version of this is that pattern of tension that we learned from Aristotle. We have an ordinary person (what is), and we have adventure that lies ahead (what could be). The transference from one to the other is the journey.

In business, the case study is a rather common way marketers use this kind of story to sell a product or service. (Most of them are a little less entertaining stories than Star Wars, unfortunately.) A case study is the story of where a customer was, where they wanted to be—the tension!—and how they overcame that gap.

If you listen to podcasts, you’ll hear this story told in most every ad. One of the most common ads is for Harry’s razors, which tells the story of “Jeff and Andy, two ordinary guys who got fed up with paying way too much for razors at the pharmacy and decided to buy their own warehouse to sell affordable razors.”

The problem with most brands’ stories is they either don’t fully utilize the four elements of great storytelling, or they don’t walk us through enough of the steps of the Hero’s Journey to capture our attention.

That’s why these frameworks are so useful. They’re a really easy way to ensure that we’re more creative when we’re coming up with stories or trying to convey information.

It’s sort of like a haiku: If we told you right now to come up with a poem on the spot, you would probably have a tough time. But if we told you to come up with a haiku about Star Wars, you’d likely be able to do it. This framework helps you focus your creativity.

Another great story template comes from comedy writing. It starts similarly: A character is in a zone of comfort. But they want something, so they enter into an unfamiliar situation. They adapt, and eventually get what they’re looking for but end up paying a heavy price for it. In the end, they return to their old situation having changed.

This is the plot of pretty much every episode of Seinfeld.

For example: During the sixth season of the show, George gets a toupee. This new situation is unfamiliar, but he likes it and quickly adapts to it. Once he has what he wants, though, he starts getting cocky. He goes on a date with a woman and behaves like a haughty jerk.

It turns out that his date, under her hat, is actually bald, too. When George is rude about this, she gets mad. His friends also get mad at him. “Do you see the irony here?” Elaine screams at him. “You’re rejecting somebody because they’re bald! You’re bald!” She then grabs George’s toupee and throws it out the window. A homeless man picks it up and puts it on.

The next day, George feels like himself again. “I tell you, when she threw that toupee out the window, it was the best thing that ever happened to me,” he tells Jerry. “I feel like my old self again. Totally inadequate, completely insecure, paranoid, neurotic, it’s a pleasure.”

He also announces that he’s going to keep seeing the bald woman. He returns to apologize to the woman, only for her to tell him that she only dates skinny guys.

So then George goes back home, having changed. He has his regular bald head now, but he’s learned a lesson. (But because it’s Seinfeld, he goes back to his old habits by the next episode.)

Both of these types of journeys are the journeys that we all go through in our lives, our businesses, and our families. As a storyteller, you can rely on these journey templates to shape your plots so you can fully unleash your creativity within.

The Ben Franklin Method

When Benjamin Franklin was a boy, he yearned for a life at sea. This worried his father, so the two toured Boston, evaluating various eighteenth-century trades that didn’t involve getting shipwrecked. Soon, young Ben found something he liked: books. Eagerly, Ben’s father set his son up as an apprentice at a print shop.

Ben went on to become a revered statesman, a prolific inventor, and one of the most influential thinkers in American history. He owed most of that to his early years of voracious reading and meticulous writing—skills he honed while at the print shop.

Franklin wasn’t born an academic savant. In fact, in his autobiography, he bemoans his subpar teenage writing skills and terrible math skills. To succeed at “letters,” Franklin devised a system for mastering the writer’s craft without the help of a tutor. To do so, he collected issues of the British culture and politics magazine, The Spectator, which contained some of the best writing of his day, and reverse engineered the prose.

He writes:

I took some of the papers, and, making short hints of the sentiment in each sentence, laid them by a few days, and then, without looking at the book, try’d to compleat [sic] the papers again, by expressing each hinted sentiment at length, and as fully as it had been expressed before, in any suitable words that should come to hand.

Basically, he took notes at a sentence level, sat on them for a while, and tried to recreate the sentences from his own head, without looking at the originals.

Then I compared my Spectator with the original, discovered some of my faults, and corrected them. But I found I wanted a stock of words, or a readiness in recollecting and using them.

Upon comparison, he found that his vocabulary was lacking, and his prose was light on variety. So he tried the same exercise, only instead of taking straightforward notes on the articles he was imitating, he turned them into poems.

I took some of the tales and turned them into verse; and, after a time, when I had pretty well forgotten the prose, turned them back again.

As his skill at imitating Spectator-style writing improved, he upped the challenge:

I also sometimes jumbled my collections of hints into confusion, and after some weeks endeavored to reduce them into the best order, before I began to form the full sentences and compleat [sic] the paper. This was to teach me method in the arrangement of thoughts.

He did this over and over. Unlike the more passive method most writers use to improve their work (reading a lot), this exercise forced Franklin to pay attention to the tiny details that made the difference between decent writing and great writing:

By comparing my work afterwards with the original, I discovered many faults and amended them; but I sometimes had the pleasure of fancying that, in certain particulars of small import, I had been lucky enough to improve the method or the language, and this encouraged me to think I might possibly in time come to be a tolerable English writer.

When he says a “tolerable English writer,” he’s being humble. In a trivial amount of time, teenage Franklin became one of the best writers in New England and, shortly after that, a prodigious publisher.

But more importantly, being a better writer and a student of good writing helped Franklin become a better student of everything. Good reading and writing ability helps you to be more persuasive, learn other disciplines, and apply critical feedback more effectively to any kind of work. When we’re hiring for Contently, our first impression of a candidate is dramatically impacted by the clarity of their emails.

After building his writing muscles through his Spectator exercises, Franklin reported that he was finally able to teach himself mathematics:

And now it was that, being on some occasion made asham’d [sic] of my ignorance in figures, which I had twice failed in learning when at school, I took Cocker’s book of Arithmetick [sic], and went through the whole by myself with great ease.6

Perhaps Ben’s little secret for learning to write isn’t so dissimilar from what MIT professor Seymour Papert’s research has famously revealed: that children learn more effectively by building with LEGO bricks than they do by listening to lectures about architecture. It’s not just the study of tiny details that accelerates learning; the act of assembling those details yourself makes a difference.

This is an excerpt from the Amazon #1 New Release, The Storytelling Edge: How to Transform Your Business, Stop Screaming Into the Void, and Make People Love You by Joe Lazauskas and Shane Snow. Order it today to take advantage of some awesome pre-order bonuses.

No comments:

Post a Comment