When Facebook shared a story in its official newsroom at 9:00 p.m. on Friday night, it didn't bode well for anyone.

Maybe it would make sense to post a small, throw-away story at a time when few people would be monitoring their inboxes for breaking news or major announcements. But at that point, why publish it at all? No, this had to be something big -- something that Facebook hoped people would miss for the sake of their regularly-scheduled Friday night plans.

But it didn't quite work out that way.

Instead, the weekend was much noisier than usual, with reporters, legislators, and executives weighing in on what might turn out to be the biggest tech news story of the year: the story of how the personal data of 50 million Facebook users was obtained by a so-called data analytics firm and likely misused for a number of purposes, including, allegedly, influencing a U.S. presidential election.

How in the world did this happen?

Many are understandably confused about that question -- as well as what's going to happen now, who's at fault, and more.

Here's what you need to know.

What's Going on at Facebook? A Breakdown of the Ongoing Data Story

What Happened?

This all began when Cambridge Analytica, a data analytics firm, began wading into the world of politics. It wanted to find an edge that other, similar consulting companies hired by campaigns, for example, didn't have -- and the solution to that was thought to be found in personal Facebook data.

That went beyond someone's name, age, email address, and demographics. It had to be behavioral data -- such items and behaviors as Page and comment Likes that would help analysts build what they called psychographic profiles that could reveal if someone was, as the New York Times put it, "a neurotic introvert, a religious extrovert, a fair-minded liberal or a fan of the occult."

That could be determined by closely examining what a person Liked on Facebook -- and could help to compose influential messaging to sway consumers ... or voters.

That helps to explain why Cambridge Analytica was hired by Donald Trump’s campaign officials leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election -- and received investments from Robert Mercer (a known Republican donor) and Steve Bannon, Trump's former campaign advisor.

The data on users' Facebook behavior could be used to shape messages that leveraged what Mark Turnbull, Cambridge Analytica's political division managing director, called "deep-seated underlying fears [and] concerns" in hidden camera footage captured by the U.K's Channel 4 as part of an investigative report.

"The two fundamental human drivers, when it comes to taking information onboard effectively, are hopes and fears -- and many of those are unspoken and even unconscious," Turnbull said in the footage. "You didn’t know that was a fear until you saw something that just evoked that reaction from you."

That's where the behavioral data came in -- it could help Cambridge Analytics do its "job ... to drop the bucket further down the well than anybody else, to understand what are those really deep-seated underlying fears, concerns."

He added: "It’s no good fighting an election campaign on the facts because actually, it’s all about emotion.”

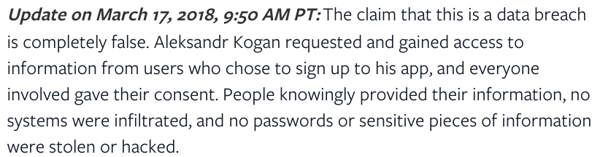

This Was Not a Data Breach

While it can be argued that this personal data was used for less-than-savory purposes, one of the biggest misconceptions of this story is that it was a breach or hack of Facebook that allowed Cambridge Analytica to obtain the personal data of 50 million users.

However, that's not what happened.

"This wasn't a data leak by Facebook," said Marcus Andrews, HubSpot's Principal Product Marketing Manager. "I think that has been misreported."

Source: Facebook

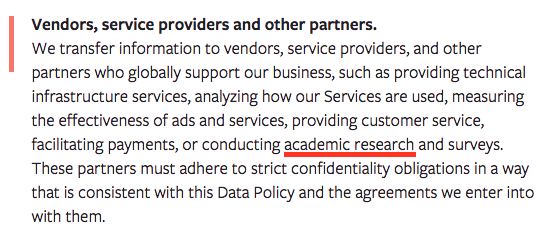

When someone creates a Facebook account, she must agree to the company's Data Policy: a rather long document that discloses the use of a user's personal Facebook data, what kind of data is collected, as well as details on how and why that data is used.

Here's a crucial, but largely unnoticed excerpt:

The "academic research" allowance played a major role in allowing Cambridge Analytica, in particular, to gain access to personal user data. At Cambridge University’s Psychometrics Centre, researchers created a method of synthesizing a user's personality elements based on the Pages, comments, and other content they liked on Facebook.

The method required users to opt-into taking a personality test and downloading a third-party app on Facebook that scraped some of that information, as well as similar data from their friends. These users were compensated for their participation in the research, and when it was conducted, Facebook permitted that type of activity on its site.

But the Psychometrics Centre wouldn't agree to work with Cambridge Analytica, so it instead enlisted the help of Dr. Aleksandr Kogan, one of the university's psychology professors. He built his own app with similar capabilities in 2014 and, that summer, started work on obtaining the requested personal data for the firm.

According to the New York Times report, Kogan revealed nothing more to Facebook and users than that he was collecting this data solely for academic purposes -- a purpose that Facebook did not question or verify. In its official statement on the matter, Facebook VP & Deputy General Counsel Paul Grewal wrote that Kogan "lied to us and violated our Platform Policies by passing data from an app that was using Facebook Login to SCL/Cambridge Analytica."

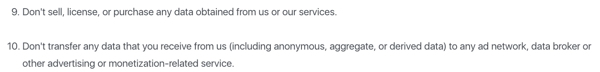

Those policies forbid third parties from selling, licensing, or purchasing data obtained from Facebook, or transferring that data "to any ad network, data broker or other advertising or monetization-related service."

On the surface, it appears that Facebook did not violate any privacy rules or standards by allowing this personal user data to be accessed. Kogan, however, allegedly violated the platform's policies by transferring it to Cambridge Analytica, where it was assumed to be used for non-academic purposes.

But it's been known since 2015 that Cambridge Analytica has been in possession of this data, when it was using it in a similar manner while working on behalf of then U.S. presidential candidate Ted Cruz, which Guardian reported on late that year. At the time, Facebook said it was “carefully investigating this situation,” and, more recently, claims Kogan's app was removed from the network and that it received "certifications" from Cambridge Analytica and Kogan, among others, that the data had been destroyed.

Why Facebook Is Taking a Major Blow

On Monday, following a weekend of emerging news and speculation around what Cambridge Analytica had done, Facebook began to experience was looked to be the beginning of a major fallout.

By the end of the day, its stock price had dropped over 7% (and continued to drop through the publication of this post on Tuesday), causing CEO Mark Zuckerberg to lose roughly $5 billion of his net worth. A #deletefacebook movement began. And by Tuesday morning, Zuckerberg had been called upon by members of the U.K. parliament to furnish any evidence pertaining to Facebook's connection to Cambridge Analytica.

But if Facebook didn't actually violate any rules, what's causing the uproar? Especially if it's hardly the first instance of data being used in this capacity?

"None of this tech is new to advertisers," says HubSpot head of SEO Victor Pan, an ex-search director who worked for one of the largest-known global media buying companies, WPP plc, for three years. "But there's an uncanny valley experience that is also true with personalized advertising -- and we're there right now."

In other words, users largely feel that they were being manipulated by Facebook -- or that, despite its emphasis on how much it values privacy, it wasn't doing enough to protect them from the abuse of their personal data.

"It doesn't feel very good to know that you're being manipulated," Pan said, "and people are turning denial into anger."

The timing of the news doesn't help, either. Facebook, as well as several other online and social networks, is already facing high scrutiny for the alleged weaponization of its platform by foreign agents to spread misinformation and propaganda with hopes of influencing the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Plus, there are rumors circulating that Facebook's chief security officer, Alex Stamos, will soon be departing the company among conflicting points of view with other executives (and the downsizing of his department). Stamos is said to have wanted greater transparency around the network's privacy and security woes, contrasting the opinions of others in the c-suite.

"It also raises the wrong questions for Facebook at a time when the company is already struggling to retain its younger user demographic," said Henry Franco, HubSpot's social campaign and brand Marketing Associate. "This is a group that is increasingly wary of how the company collects user data."

And for his part, Andrews says that more users should share this concern and skepticism. "From a user perspective, people shouldn't assume their social data is in any way protected," he explained. "All the data you provide social networks is manipulated, shared, and monetized constantly -- illegally and legally."

What Happens Now

As a first step, Facebook banned Cambridge Analytica and other associated actors -- including Dr. Kogan and Christopher Wylie, the contractor working with Cambridge Analytica who is said to have blown the whistle on the alleged use of this data by the Trump campaign.

Suspended by @facebook. For blowing the whistle. On something they have known privately for 2 years. pic.twitter.com/iSu6VwqUdG

— Christopher Wylie (@chrisinsilico) March 18, 2018

As for the uncertainty of earlier certifications that the user data was destroyed after initial revelations in 2015, Facebook has enlisted the services of digital forensics firm Stroz Friedberg to determine if the data is still in existence, or in Cambridge Analytica's possession.

However, Stroz Friedberg investigators have since stepped aside to make way for an investigation being conducted by the U.K. Information Commissioner’s Office.

As the story continues to unfold, there appears to be much at stake for marketers and those who use social media -- as well as data -- to shape messaging in a legal way. In fact, Andrews says, the use of social data to personalize marketing isn't always a bad thing: "It keeps the internet free and makes the ads and content you see more relevant."

But he cautions of the consequences that marketers could ultimately face because of the actors who use data maliciously, citing a "need to better understand the power these data can provide people with an ulterior motive, and protect consumers" accordingly.

That's especially true in the face of such regulations as the GDPR, which is coming into force in the EU next month. And now that the U.S. is experiencing particularly amplified cases of personal data abuse, Andrews says, it "could speed up internet privacy regulation and provide fodder for lawmakers who want that. We could be headed towards a more regulated digital marketing landscape."

But until that day comes, says Franco, it's up to the rest of us to ensure that user data is protected.

"With very little government regulation, it’s up to tech giants to enforce these rules, which highlights a huge conflict of interest," he explains. "Any restrictions on how third parties take advantage of user data could potentially impact their profitability."

And, he suspects, this event is likely the last we'll see of personal data use coming into question.

"With so many third-party developers able to access user data through Facebook APIs, there’s no telling how many other actors might be abusing data in a similar way," he says. "While the Cambridge Analytica situation is unsettling, what’s worse is that it may just be the tip of the iceberg."

This is a developing story that I'll monitoring as it unfolds. Questions? Feel free to weigh in on Twitter.

No comments:

Post a Comment