It's not often that I leave a tech conference keynote feeling like I had just attended an academic seminar in which I had mistakenly enrolled.

Of course, being a natural cynic, I have left them with skepticism. Will that product actually ever roll out? Does the technology really work the way it appears to in video demos?

But today's opening keynote at Oculus Connect -- Facebook's annual virtual reality (VR) mega-conference -- was different. I left not feeling incredulous, but rather thinking to myself, "That ... was anticlimactic."

The Timing of Oculus Connect

It's been a dramatic week for Facebook.

On Monday, it was revealed that the co-founders of Instagram -- which was acquired by Facebook in 2012 -- were stepping down. (Oculus, for context, was acquired by Facebook in 2014.)

Today, Forbes published a controversial interview with Brian Acton, the co-founder of WhatsApp who departed the company earlier this year, only to prompt a contentious response from David Marcus: the former VP of Messenger who now oversees a small Blockchain group at Facebook. WhatsApp is also among Facebook's acquisitions.

Maybe it was the context of a week of concentrated executive theatrics --among what has been a year of turmoil and bad PR for Facebook -- that not-so-subtly caused the anti-climactic sentiment of today's keynote.

But more than that, as others have been keen to point out, it could have been caused by the seemingly "slow roll" of VR, which the public has been slow to receive in a tangible way, and whose user base still largely consists of early adopters.

Oculus' annual #OC5 conference feels anti-climactic as slow VR adoption and tech advances minimize progress. These Expressive Avatars are cool, but there aren't enough VR owners to use them https://t.co/hxGRz3IVyz pic.twitter.com/AF99M9tJVN

— Josh Constine (@JoshConstine) September 26, 2018

Looking Back, Looking Forward

The Road to One Billion

At last year's Oculus Connect, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg waxed bold about his goal of one billion people using VR, though by when, he didn't quite say. Today, almost laughably, he pointed to the reality -- no pun intended -- that he's less than 1% of the way there.

Zuck is feeling funny today. Here’s a graphic showing the progress to his projection/goal last year of getting 1 billion people into VR #oc5 pic.twitter.com/hsHmmIo0s9

— Amanda Zantal-Wiener (@Amanda_ZW) September 26, 2018

But in order to get to one billion, Zuckerberg said, the "how" needs to be prioritized over the "when." And that, he explained, requires a better overall VR ecosystem -- to get more users on each Oculus headset, and to build the technology in a way that allows new models and platforms to cooperate with old ones.

I like to think of this concept in terms of iPhones -- how older models of the device tend to stop working as well as newer generations of the iOS are loaded onto it. In order to make the market for VR truly permeable, Zuckerberg said, the platforms can't work that way.

So, what does that look like -- today, at least? It starts with the Oculus Quest: the company's "first all-in-one VR system ... that lets you look around in any direction and walk through virtual space just as you would in the physical world." It will ship next spring -- at Facebook's annual F8 developer conference, I predict -- and comes with a $399 price tag.

But is that really the way to the hearts of the non-early-adopter's heart -- a nearly-$400 price tag on hardware that many people haven't even started tinkering with?

People First

After Zuckerberg unveiled the Oculus Quest, Facebook's VP of Consumer Hardware took the stage to discuss the responsibility of tech to put people first -- to use developments like VR to break down distance and barriers between people, rather than silo them.

But it seems that the focus on connecting people in this realm seems to be, if you'll excuse the play on words, virtual. The Oculus's gaming capabilities and features like Oculus Venues -- which allows users to "attend" live events like sports games and concerts in VR -- does connect people and allow them to use VR in a social way.

It's still purely online, however -- arguably siloing users in a virtual world that doesn't invite human interaction in a way that our species has evolved to exist and function.

And should VR go mainstream -- it's that potential encouragement of "getting inside and getting online" that I find most worrisome about its future.

A Future of VR That Doesn't Shine So Bright

What We Expected

When I outlined my key predictions for Oculus Connect yesterday, I was perhaps approaching it from an over-optimistic point-of-view (which, if you know me at all, is out of character).

I had hoped to see more use cases for VR that involved training people in the workplace, of helping them get to know each other in a safe (virtual) environment before meeting in person -- a possible integration with Facebook for Dating -- and donating VR headsets to underserved schools to aid learning.

But what we heard today didn't reflect that. Instead, we received one major announcement -- the future launch of the Oculus Connect -- a heavy emphasis on new gaming features, and an extensive history lesson on how Big Tech came to be, and how it will dictate VR's future, from Oculus Chief Scientist Michael Abrash.

What We Got

The man clearly has a lot to say -- "once Abrash gets started, all bets are off" I heard a PR rep say in the press lounge later -- and seems bullishly optimistic on the future of VR.

In a few years, that is.

In order to make the mass market for VR truly permeably, Abrash suggested, it has to become a social norm. That is, it has to be accessible and acceptable in a way that allows it to be used any where, any time -- including in public.

Part of that future -- which Abrash says he foresees coming true within the next four-to-five years -- includes modifications to both the technology and the hardware. Here's where he started to lose me ... and others.

I no longer understand what’s happening at this Oculus event 🤘🏼 pic.twitter.com/OIyG8k99od

— Kurt Wagner (@KurtWagner8) September 26, 2018

First, the technology has to evolve to be able to mix different layers of reality, Abrash said. It has to allow users to enjoy VR experiences in a "see-through" way that also allows them to see the physical environment around them, sometimes combining the two.

It also has to integrate what we do on our other devices, such as our phones, where we receive message and social media notifications.

A look "under the hood" of the Oculus Connect. This image depicts how the technology/camera combines in-real-life object detection with the position of the user to overlay VR features with that environment #oc5 pic.twitter.com/LNQiovgm9h

— Amanda Zantal-Wiener (@Amanda_ZW) September 26, 2018

And for the hardware, it has to be okay to wear in public without 1) walking into trees, walls, and other people, or 2) looking weird. That means that the ultimate mixed reality headset -- the one that truly leads to a mass adoption of VR -- can't be a headset at all. It has to be a pair of glasses.

The Many Sides of VR Coming to the Masses

As with most emerging technologies, there are both positive and negative sides to a future where, as Abrash put it, we're able to "combine the real with the virtual whenever you want."

On the plus side, you have benefits for those with something like panic disorders: a future in which these users instantly converge something calming, like a positive environment replete with a guided breathing exercise, with the actual environment or situation around them that's causing panic.

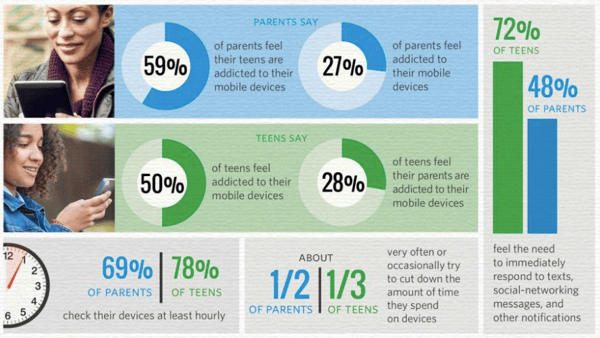

But when evaluating the drawbacks of such usability, I point to the fact that so many of us -- myself included -- already engage in the unhealthy habit of constantly looking down at or checking our phones, no matter what we're doing or who we're with.

Now, layer that present reality with the future one -- where we're already over-connected, but are also potentially both existing in silos from real-life engagement with others and, even when we do venture into public, can easily replace what's actually happening around us with a virtual "improvement"?

It's a future that's a bit of a way's off -- and that's even if Abrash's vision of mass consumption of VR comes to fruition -- but if so, the long-term implications should be considered.

Technology has already caused us to evolve to a point of being addicted to mobile devices in a way that's diminished our attention spans and empathy -- especially among younger generations who could actually live to see this future.

Source: Common Sense Media

Should this future come true -- one where we can quickly overlay actual reality with something that we prefer -- also evolve us to the point of no longer being able to cope with conflict, stress, or other scenarios in which we've historically relied on survival instincts?

Many other things would need to happen first. More people would have to start using VR, perhaps at the extent to which we use smartphones. More people will have to be able to afford it, too. And there might have to be rules, too -- perhaps within the same vein of barring texting while driving, or using phones in the classroom among a certain age group.

But again, these possibilities should be considered. If Oculus truly wishes to put people first, and bring us back to the human side of technology -- its long-term impact on the very people into whose hands these products will go should be carefully and thoroughly evaluated.

We'll be at Oculus Connect tomorrow, too. Check back for our coverage of Day 2.

No comments:

Post a Comment