Introducing "Posts as a Podcast": Explore something new on your daily commute, at the gym, or from the comfort of your desk. We're turning our favorite posts into bite-sized podcasts for your listening pleasure. So grab a cup of coffee, sit back, and let us tell you a story.

Once upon a time, in a land that some of us are so lucky to remember, people had to leave the house to buy music. We would count down the days until a new album dropped, and sometimes, we would even line up outside of the record store to make sure we could get our hands on a copy -- because, believe it or not, there was a time when albums actually sold out.

Yes -- I'm speaking of the era when music wasn't a downloadable, streaming product.

And it really wasn't that long ago, either. I remember the days before CDs became a commodity, before I even started buying my own cassettes, when the walls of my childhood home were lined with shelves just crammed with vinyl records. I had a box of my very own 45s. I couldn't dream of a day when, to get the latest music or even learn about new artists, I wouldn't have to go out or even turn on the TV. That information would be presented on a computer.

But music consumption has a far, far greater history than the days of classic record stores and 45s. It has prehistoric roots that somehow led to an era in which we enjoy multiple online and mobile options for listening to, well, pretty much whatever we want. So, how did we get here? It's a fascinating tale -- with a remarkably fast plot progression.

From Napster to YouTube Music: The History of Internet Radio

Live Performance

Source: Brygos Painter Français, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: Brygos Painter Français, via Wikimedia Commons

Historians believe ancient humans created flute-like instruments as part of hunting rituals and primitive cultural gatherings. It’s estimated that this earliest form dates back about 35,000 years.

From there, live music progressed through ancient Greece, where it was an essential part of different celebrations and life events, like weddings, religious ceremonies, and funerals. It’s said that the Greeks of this era were responsible for inventing many of the fundamental elements we use to compose music today, like octaves, as well as terms like “scale” and “diatonic.” Much of that was built upon in ancient Rome, where the Greek fondness of attending and spectating at live events in amphitheater-like settings was shared.

People began recording music by hand -- that is, what we today think of as sheet music. Before the sound itself could be captured mechanically, written instructions existed on how to reproduce pieces of music that were previously played. Some estimate that this practice dates back to the Babylonian era, between 1250-1200 B.C.

But many scholars say that our modern traditions of live music truly began in the European middle ages, when churches served as venues for what could be deemed live performance. Sacred melodies like Gregorian chants and the growing presence of pipe organs in houses of worship paved the way for classical composers like Johann Sebastian Bach, whose earliest work was often written and performed in churches.

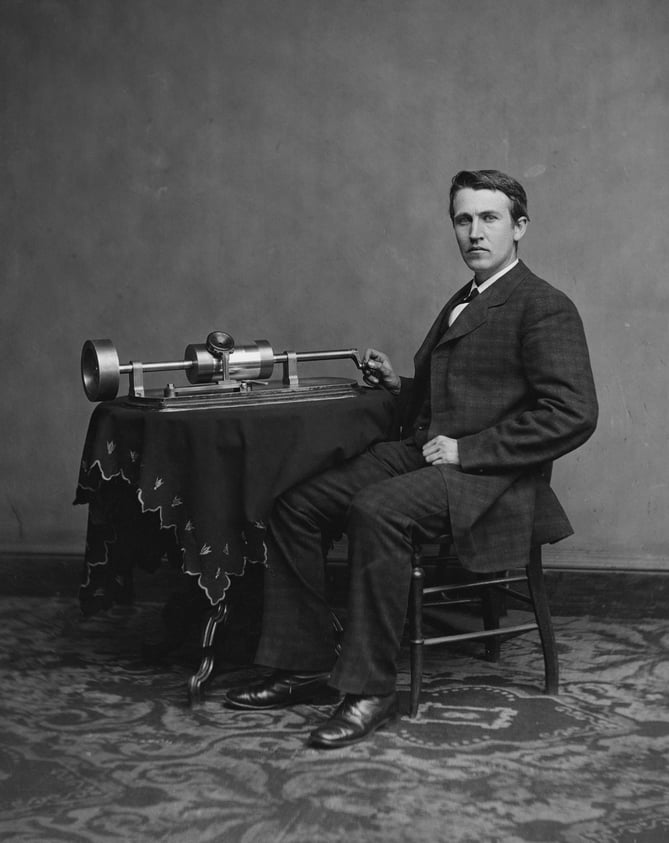

Eventually, there was a desire or idea to consume music outside of a venue, and to be able to hear it without someone else performing it in front of an audience. That’s where an inventor -- who you might have heard of -- comes in: Thomas Edison.

Records

The Phonograph

Source: Levin C. Handy, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: Levin C. Handy, via Wikimedia Commons

Surprisingly, Edison didn’t set out to create the phonograph as a way of consuming music. Rather, its 1877 invention was more of an expansion upon his earlier work on the telegraph (invented by Samuel Morse) and the telephone (invented by Alexander Graham Bell and Antonio Meucci). He thought that a spoken message -- like a verbal version of a telegraph, but recorded -- could be captured and reproduced. As it turns out, it worked, which he found out after testing a rhyme on the earliest prototype.

But when Edison published “The Phonograph and Its Future” in an 1878 issue of the North American Review, he hypothesized, “The phonograph will undoubtedly be liberally devoted to music. A song sung on the phonograph is reproduced with marvelous accuracy and power."

He was right. Within a year, “pre-recorded cylinders” -- what we know as records -- were being sold, and as they became more popular, their manufacturing was improving for multiple plays until they were finally made in vinyl -- though that format wasn’t available until after World War II.

But not long after these were available for sale -- around the 1890s -- phonograph parlors were established, were patrons could pay a nickel to listen to a recording. It was a precursor to both the record store and the juke box, and could be called a milestone in the evolution of music consumption.

The Record Store

.jpg?t=1488977396315&width=365&name=oldspillerscroppedsmaller3%20(1).jpg) Source: Spillers

Source: Spillers

Spillers, a record store in Cardiff, U.K., claims to be “the oldest record shop in the world.” It was founded in 1894, within the era of phonograph parlors, for the “sale of phonographs, wax phonograph cylinders and shellac phonograph discs.” The store still exists, but has since relocated. The oldest U.S. record store, Pennsylvania-based Bernie George’s Song Shop, was established in 1932, and also continues to thrive -- it even now boasts two locations.

Some speculate that musical recordings came second to a song’s sheet music. In Vinylmint’s written history of the industry, it’s said that “the music business was dominated not by major record labels, but by song publishers and big vaudeville and theater concerns.” People wanted to reproduce the music to play it themselves, it seems, and listening to a recording of it was almost a consolation prize. But as the record technology improved -- and the stores selling them grew in number -- they became more popular.

Vinylmint also claims that the contemporary practice of signing artists to labels began in 1904, when an opera singer named Enrico Caruso signed with Victor -- today known as RCA, a subsidiary of Sony. The roots of Victor are fuzzy at best, but according to The Fabulous Phonograph, it was founded in 1903 as the Victor Talking Machine Company. But Caruso’s signing was a precursor to the Copyright Act of 1909 that required record sale royalties to be paid to the writers and publishers of songs, but not to the people who performed them. Perhaps it had something to do with the $5 million in sales that Caruso earned for Victor.

But 1909 didn’t see the end of copyright and royalty issues -- future digital distributors of music would find themselves in sticky situations because of them, once they came to fruition. It also wouldn’t see the end of financial implications for record producers -- thanks, in large part, to the onset of music being played on the radio.

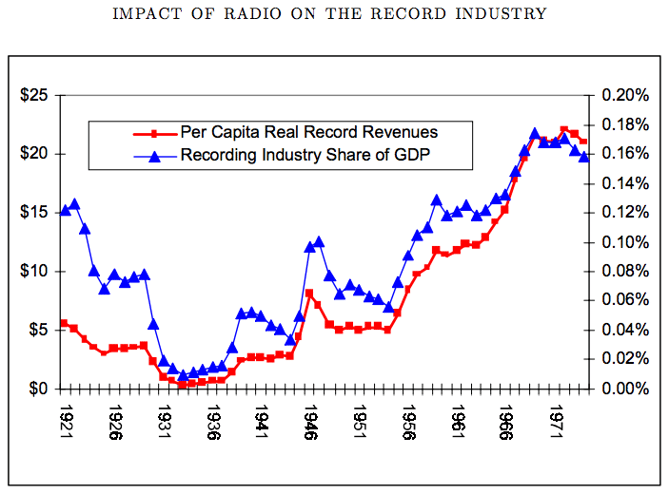

Broadcast Radio

Although radio technology had existed long before, the alleged first commercial American radio station, KDKA, didn’t begin broadcasting until 1920. Within the next six years, five million U.S. families were said to own broadcast radios. Keep in mind that the years prior to KDKA -- between 1914-1921 -- saw a 2X growth in overall record sales. But by the time music comprised much of what was played on broadcast radio (roughly 66%), record sales were beginning to see a massive decline, especially in 1929. It's worth noting, however, that the record sales decline might have had something to do with the Great Depression beginning that same year.

Source: Stan J. Liebowitz

Source: Stan J. Liebowitz

Eventually, the recording and broadcast industry found a way to work together -- otherwise, we wouldn’t be able to listen to music on the radio today. But this history shows that the distribution of music can be tricky, with major implications for both the listener and the businesses behind it.

Music Consumption Formats

Vinyl and Cassettes

Source: Malcolm Tyrrell, via Wikimedia Commons

Source: Malcolm Tyrrell, via Wikimedia Commons

So, who here remembers the cassette tape? I do. Anyone else remember holding a microphone from a tape recorder to the radio, in order to have your very own copy of the songs broadcasted? Ah, memories.

But before there was the cassette, there was the vinyl record, which was actually the result of limited manufacturing supplies during World War II. Because “shellac supplies were extremely limited,” explains the Record Collectors Guild, and vinyl was generally cheaper and more widely-available, “records were pressed in vinyl instead ... for distribution to U.S. troops.”

In the 1960s, the listening medium continued to evolve, with more options being offered, like the Philips compact cassette. It was one of the earliest formats of portable music listening -- but the real game-changer may have been the eight-track tape, invented in 1964 by Bill Lear. Soon, tapes could be played in cars -- and in 1979, Sony debuted the first major portable cassette player: The Walkman.

Compact Disc

At first glance, 20-30 years might seem like a long timespan. But in the context of technological developments, it’s actually fairly short -- and also roughly how long it took for cassettes to cease being the dominant music consumption format. That was due to the introduction of the compact disc, a.k.a., the CD. A major turning point took place in 1981, when ABBA’s The Visitors was the first pop album pressed to CD. By the following decade, economies of scale led to CDs being the primary music consumption format, with similar portable playing options -- like in-car players and the Discman -- emerging.

Vinyl never went extinct -- it’s still a prized possession for many collectors, DJs (since it provides a “direct manipulation of the medium”), and a cultural population called hipsters that’s known for its love of vintage items. Plus, audiophiles have long claimed that the quality of sound from vinyl is simply superior to other formats, especially as record-pressing technology continues to improve.

Record Store Alternatives

Around the era of CD rule, something interesting happened -- businesses began offering alternatives to buying music from a record store, or even having to leave the house to obtain it. One of the first developments in that direction was the invention of the now-defunct 1-800-Music-Now, an order-music-by-phone hotline, in 1995. But it didn’t last long, and two years later, it ceased operations. That sequence of events was mentioned in the 1997 Economist article “Tremble, Everyone,” which warned of the internet cannibalizing nearly every industry -- music included -- by introducing online buying options.

Today, that’s almost eerie to read -- perhaps because a world without the option to digitally procure music is difficult for many of us to remember. And four years later, the iPod was born, which may have permanently revolutionized the consumption of music.

The (Permanently) Digital Era

Source: Pixabay

Source: Pixabay

It Started With File Formats

Before the invention of the iPod, there was the late 1980s creation of the MP3 -- “a means of compressing a sound sequence into a very small file, to enable digital storage and transmission.” And although it’s far from the only audio file format available today, its introduction prompted a larger conversation about the digital transfer and consumption of music.

That was seen as an opportunity by Shawn Fanning, John Fanning, and Sean Parker -- the people who invented Napster: “a simple, free peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing service,” and perhaps the first of its kind to have a household name, which rose to multi-million usership by 2001, the same year the iPod was unveiled. Dann Albright of MakeUseOf hypothesizes that its alignment with the market penetration of MP3 players could be a major factor contributing to Napster’s rise to fame. Plus, it was free. Apple didn’t unveil the iTunes Store until 2003, and even then, each song cost $0.99. Sure, it came with a price tag -- but it was legal.

Napster’s practices weren’t. It came under very public fire by the music industry, and despite its effort to promote the brand with a free concert series, it could be argued that the brand never truly recovered. It underwent many changes, but is today alive and somewhat well.

And Then, Radio Came Back

Despite its own instability, Napster set the tone for continued opportunities in the realm of streaming music. The iTunes Store continued to expand its music library, and also began offering paid movie and TV show downloads. But developers and entrepreneurs alike began creating solutions to the problem presented to many by iTunes -- the ability to discover new and listen to music digitally, without having to download song files or pay-per-track. Thus, internet radio was born.

Many point to Pandora -- a free, personalized online radio app -- as the true pioneer in this space, but it came to fruition around the same time (the early 2000s) as a few others offering similar services, like Last.fm. But these apps didn’t just provide a simple service. They were starting to get smart about algorithms -- hence the personalization element. By indicating that you liked a particular song or artist, these new services had developed the algorithmic technology to figure out what else you might like, and stream it automatically.

Plus, they were able to monetize -- fast. It wasn’t long before Pandora was airing ads between songs, and eventually offered a paid, ad-free option for listeners.

But a lot of progress was being made in the space, and in a short period of time. The 2007 release of the iPhone was even more of a game-changer, with these formerly desktop-only apps offering a mobile option. That made it rival iTunes even more -- consumers weren’t beholden to Apple for music download or streaming options. That effect was exacerbated by the premiere of Spotify the following year, which now outranks Pandora. Like the latter, Spotify offers both a free and premium (read: ad-free) version.

More Music, More Money

There’s been some discord among artists as to how profitable Spotify is for them. Some, like major artists, get a significant payout, while others aren’t so sure of their gains. But if for no one else, this digital (r)evolution seems to have been profitable at least for the likes of Spotify, which is even stirring talks of an IPO and valuation in the billions. That’s partially because the revenue isn’t just coming from ads and membership fees anymore. It’s built partnerships with multiple corporations and brands ranging from the New York Times to Starbucks. It’s even co-marketed with the TV show “Mind of a Chef” for a special promotion.

And It's Only Getting Bigger

Today, streaming music options are hardly limited to Pandora and Spotify. Apple Music entered the landscape in 2015 with its own (paid) radio and subscription options, and YouTube was quick to follow suit with its YouTube Music App (Apple | Android) in 2016. Plus, let’s not forget the often understated Amazon Prime Music.

It’s hard to believe this journey began in a prehistoric era with a flute made of bones. But my, what progress the past few thousand years have shown. Even when I asked my colleagues if they remembered having to beg their parents to drive them to a record store back in the day, it seemed like a celebration of nostalgia. “My first album was ‘Tommy’ by The Who,” said our Art Director. “Mine was the Space Jam soundtrack,” remembered our Senior Video Editor & Animator. And mine? There were too many trips that I begged for to count -- though I do recall once disrupting a family vacation with my insistence on finding the latest KoRn album.

My point being, while this mind-blowingly rapid advance of digital music might seem borderline scary, it does bring us that much closer to something by which we’re all influenced: Music. And maybe, with a growing number of ways to experience audio in our day-to-day lives will come a growing number of memories made possible by a particularly great song -- old or new.

In any case -- we’re listening.

What’s the most remarkable part of the digital music evolution to you? Let us know in the comments.

No comments:

Post a Comment